Abstract

Distinguished French concert composer and pivotal figure in electroacoustic concert music, Pierre Boulez (b. 1925), produced in 1981 the musical composition Répons as a signature work for IRCAM, France's premiere facility for research in digital and musical sound, and a showpiece for one of the world's first real-time digital music processing systems, the 4x. As such, Répons represents a source of analytic richness on a variety of levels.

Thesis

Répons is primarily a spatial work that deals with sound trajectories by placing the soloists on separate equidistant platforms. This unique layout of musicians facilitates sound spatialization and the diffusion of computer transformations. The music acquires physical qualities from the properties of the musical material whose rotational speed is derived by the loudness of the acoustic sounds played by the soloists. The integration of electronics, acoustic sounds and space, makes Répons a logical step for Boulez's ideas on the organization of music. Boulez uses technology devised by him and developed by a team of computer scientists, engineers, and composers at IRCAM (Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique) during the 1980's to produce a work that revolutionizes the concept of the concert hall, accordingly to Boulez's ideas. By using real-time synthesis and spatialization, Boulez creates a “virtual” cathedral realizing an old idea while reflecting on two Bach chorales.

This study explores the electronic innovations that realized Boulez's vision, examining how the composer integrated morphological and syntactic elements with live electronics to create a unique sound space. The resulting work is both musically and visually striking, drawing inspiration from medieval musical traditions and incorporating global musical influences.

Pierre Boulez, IRCAM and Répons

After World War II, and without trying to justify the steps that led to a multitude of styles and lack of innovation of our immediate predecessors, Boulez calls for a new establishment and the creation of new grammar and language: a new solid foundation for contemporary music. This foundation should bring long-term solutions trying to avoid being a simple architectural fashion. Like any established language, it should address its long-term solutions of formal and linguistics problems. Beginning with questions of aesthetics, after a codification (serialism) of the language, composers moved to as many different directions as personalities, sometimes, in great opposition to each other. (Boulez 1986 , p446)

Boulez's critique of contemporary music trends highlights a divergence from his envisioned path for musical evolution. He observed a proliferation of diverse approaches that, in his view, often masked regressive inclinations. Boulez argued that many composers were essentially recycling past ideas under the guise of innovation, rather than genuinely pushing the boundaries of musical expression:

What am I trying to say about contemporary music? That there are a lot of different tendencies -- but I must eliminate from the start all that are backward-looking, all "restorations", which are not so much tendencies in fact as nostalgias. (Boulez 1986 , p447)

The composer's stance reflects a desire for a forward-looking, unified direction in contemporary music. He sought to distinguish between genuine innovation and what he perceived as nostalgic retreats to familiar territory. Boulez advocated for eliminating these "restorations" from consideration as valid contemporary tendencies, viewing them instead as manifestations of personal longing for past musical forms.

This perspective underscores Boulez's commitment to forging a new musical language that would break free from historical constraints. His vision for contemporary music emphasized the need for authentic progression and the development of novel compositional techniques, rather than repackaging traditional elements in modern wrappings.

But Boulez's primary preoccupation was the unity and co-coordination of activities among different fields. Boulez was a visionary, who looks for a return to the future trying to find a universal language to give contemporary music the chance to become truly universal. He looks for a general organization of music and its relationship to the public instead of falling into the dialectics about the contrasts between electroacoustic, acousmatic and instrumental music. Recognizing the difficulty of the problem and calling for a multidisciplinary effort, Boulez proposed changes such as building new and specialized concert halls without orchestras, but instead with a consortium of performers getting rid of expanded nineteenth-century norms that can only perform old repertoire making it difficult, if not economically impossible, to play contemporary music. (Boulez 1986 , p448)

"As a composer who enjoys music from different parts of the world as much as European music, listening to Japanese Gagaku or Noh, Indian, Balinese or Aztec music, is to me as satisfying an experience as listening to European music". (Boulez 1986 , p449)

The composer views this museum-like tendency as a wall to incorporate other cultures and to form an opinion of examples of our own contemporary evolution; without altering our present conception of musical life, it is impossible to put today's audiences in contact with the creative forces at work, of course these forces include the design of new concert halls and a system that allows for an alternative to the old-fashioned orchestra. Only then, the specialized public who only listen to classical music or music from the renaissance, or contemporary music, will be able to support their own museum-like activities with forward-looking tendencies or current activities.

For the most part --and I feel very strongly about this-- these specialized publics, whether it be for contemporary or baroque music, specialist conductors or specialist performers, are all specialists in nothing, because they are incapable of corroborating their own special interest with present day activities. And until we have the means for this practical synthesis, our musical life will continue to lack any real sense. It is not possible to judge simply as a specialist, as one might judge Chinese prints (Boulez 1986 , p449).

Boulez is not only criticizing the supporters of museum-like settings for music; the concert hall itself is a problem where more time is spent arranging the space for each piece than the music itself. The concert hall becomes something that is impeding the musical flow of the performance and the music is presented as an object of contemplation thus the audience does not take any part besides contemplating the masterpiece. Boulez asserts that the concert hall is no longer necessary because there are no masterpieces in contemporary music, there are no fixed forms, no rules regarding the number of performers or orchestral forces. In so rigid a framework as this, the concert form is no longer really necessary, as performance is perpetually interrupted and any desire for communication will simply be frustrated. (Boulez 1986 , p450)

The same is true for new electroacoustic music or electronic (tape) music where the audience sits facing loudspeakers and in some cases the lights are turned completely off. There is no regard for the visual aspect or interest of the performance. The same effect can be achieved by playing a record in a room with friends or a small group. Closing the eyes, falling asleep or lack of attention are the inevitable results of these dull performances unless there is something to see or some deduction to be drawn. Boulez proposes many ideas to solve the problem of communication between audience, performers, loudspeakers and contemporary music. Firstly, in order for an audience to accept something new without knowing the number of conventions there has to be a way to synchronize the visuals with the music. 1

In opera, the first thing that takes our attention is the mouth of the singers. We are aware of this, we accept it, and then we focus our attention to the music. Electroacoustic music, especially when electronic sounds are not synchronized to the physical gestures of performers, creates a challenge to our senses and expectations, thus, taking our attention. Seeing one thing and hearing another will get our brain working for a moment. This is especially true for real-time and interactive music where the members of an audience will try to decipher the correlation or mapping between physical gesture and the sounds coming from loudspeakers. As a composer/performer, one must be careful not to confuse gesture with gesticulation and not to get music accepted for other elements that are secondary and have nothing to do with music.

Another problem in contemporary music is architecture, not the architects, who have not been given the opportunity to design concert halls for new music. 2 The Berlin Philharmonic is an example of a new design with its vineyard-style seating arrangement, and it became the model for other concert halls, such as the Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles and the Disney Opera House. According to Boulez, the whole central conception remains unaltered. The conception of music as an object of worship does not change with these new "old" designs. In fact, each member of the audience is overwhelmed by the architecture whose layout makes any participation impossible. Putting a large piece of modern sculpture in the main foyer or having a flying-saucer ceiling will not alter the sense of a hall. (Boulez 1986 , p452)

Boulez felt that these circumstances led to the creation of a number of small niches that did not have direction and therefore remained scattered and isolated as composer and performers tried to experiment without a lab, and without the means to communicate with the audience. Without promoting false solutions to solve the problem, starting in 1953, Boulez organized avant-garde concerts with the idea of letting the public judge certain things. The idea was to create a well-educated public and to do musical experiments that sometimes were not successful but were good enough for giving the audience something to judge.

Boulez is also concerned with science and the relationship between aesthetics and technical problems. He thinks all electronic music studios failed simply because of lack of coordination between engineers, composers and musicians. That is to say, there was no collaboration between the inventor, experts and players. He thought that no serious work had been done between these collaborations or established a relationship between science and music. Music is not science, it is an individual means of expression and lacks scientific rigor but according to Boulez, the language has not been put under the microscope for almost two centuries.

To create an understanding between multiple disciplines, there is a need for a laboratory where researchers can find solutions to the problems mentioned above. Electronic and electroacoustic music creates the need for the expansion of instruments, therefore the intervals found in Western music. It is possible to obtain sonorities from sources other than vibrations from objects. The creation of these machines require a collaborative effort between scientists, engineers and artists. Although many electronic or electroacoustic studies have been written, Boulez criticizes the lack of aesthetics mainly from the angle of the material itself, and emphasizes how satisfying it is to discover sounds and sonorities and that are transformed into something that has never been heard before. (Boulez 1986 , p46)

In his major work Le marteau sans maitre (1952-5), Boulez already shows his ideas regarding new orchestral combinations to create new sonorities, especially those unfamiliar to the niche listener. Favoring resonating instruments in the middle range (guitar, marimba, viola, alto flute, vibraphone and percussion) which are typical of the Boulezian instrumentarium for their capabilities of producing a continuum of sonorities, the composer may be evoking the music of Japan, Central Africa and Bali. Although part of his compositional style, the idea of the continuous sonority also found in Eclat (1965) finds its acme in Répons (1980-1984).\ After Le marteau sans metre, the first unsuccessful attempt to create a dialogue between an orchestra and a tape was Poesie pur pouvoir (1958). The composer, who considered the tape part inadequate, withdrew it from the catalog after its first performance. (Goldman 2011 , p10)

Perhaps this unsatisfying experience with regards to electroacoustic and electronic music and Boulez's interests on finding new sounds led to the creation of IRCAM, an autonomous institution devoted to the research and development of sound and music with emphasis in real-time interactions between technology and musicians. "IRCAM must be created as an institution, which is to have musical research as its function, acoustics as its subject, and the computer as its instrument". Boulez was never attracted to working with a tape that is synchronized with the performers, such as in Davidovsky's Synchronisms (Jameux 1989 , p169) 3 4 5

In addition to the difficult task imposed on the untrained performer, the act of synchronizing with a click track or by carefully studying the piece, may act against the musical flow constraining the expressiveness of a performance; in the case of a piece for a larger ensemble or orchestra it would hinder the role of the conductor.

Well, of course in the beginning, my experiences with electronic music were fraught with difficulties. I had rather bad experiences with the medium of tape music, and listening to loudspeakers in general was not at all satisfactory. But what was really restrictive from my point of view was the idea of the performer following the tape in a kind of straitjacket, which I found to be very detrimental to the performance in general. It was because of this that I pushed research at IRCAM toward live electronics. In this way I wanted the electronic element (which over the years had evolved to the use of computers) to be geared toward the concert situation. (DiPietro 2001 , p67)

This preoccupation with "real-time electronics" was put into practice in several works such as Dialogue de l'ombre double (1985), ...explosante-fixe...(1973-74), Anthèmes 2 (1997), and Répons. 6

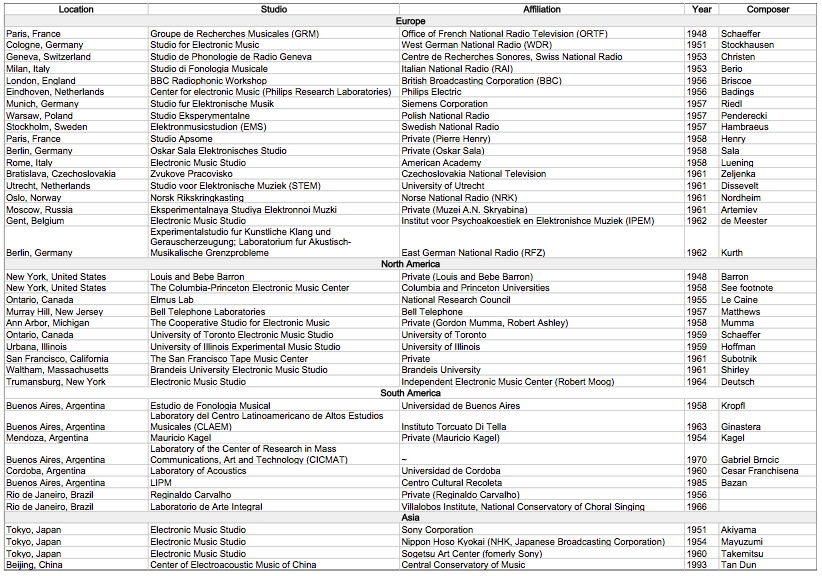

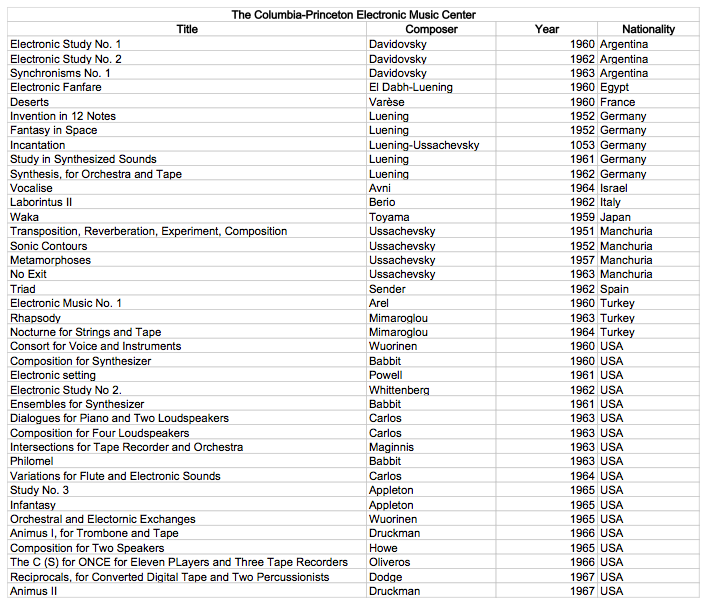

The idea of an institution for sound research was not new for Boulez or the French. There were many experimental sound studios around the world such as GRM in France, and other institutions and radio studios outside France such as the Studio di Fonologia Musicale di Milano in Italy (1953), and Studio for Electronic Music (WDR) in Cologne, Germany (1951). 7 Perhaps the most "international" studio was the Columbia-Princeton, which attracted composers from many different countries, most notable the Argentinian Mario Davidovski. 8 These studios and the hundreds of studios that were created around the world during the 1950s and 60s mainly focused on the production of musique concrete (Shaeffer) or electronische musik (Stockhausen). On the other hand, IRCAM, although with roots in the French tradition focused --still today-- on technological research and real-time electronics. 9

The institution was inaugurated by Boulez in 1977 with negotiations with the French government going back to the 1960s. This unique organization took a cross-disciplinary path involving composers, scientists and engineers. Boulez assembled a remarkable team including Luciano Berio, Jean-Claude Risset, Vinko Globokar and Max Mathews. The institution, part of Centre Georges Pompidou, created hardware and software for the transformation of sound in real time such as Max, the precursor of Cycling'74 Max/MSP10 and Pure Data (PD)11 developed by Miller Puckette in the mid-1980s at IRCAM. (Goldman 2011 , p11) 12

Max is the result of Boulez wanting to make computer languages more intuitive for the composer who does not think in terms of hertz, and does not have the patience to wait hours for a computation to finish--something that engineers and technicians might enjoy--. Boulez's ideas about technology and a multidisciplinary collaboration between scientists and musicians changed as the institution grew and more scientists-musicians or musicians with a great understanding of computer science were favored by the seven research teams IRCAM has today. 13

One of the first pieces of hardware developed and created at IRCAM was the legendary 4x and the Matrix 32, a computer (instrument) that was used in Répons and deserves special attention. In addition to sound generation using additive synthesis, envelope following, frequency and ring modulation, both computers were also used for spatializing sounds in real-time, something that was groundbreaking at the time.

The 4X

Introduction

After decades of analog computers capable of processing only data and with the innovation of the first integrated circuits in the 1960s, a new digital era began. Moreover, in the 1970s, Intel Corporation invented the microprocessor, placing the Central Processor Unit (CPU) in a single chip of silicon about the size of a fingernail. After that, computer chips became smaller and faster; by the late 1970s the means for processing digital signals in real time were already developed. In 1977, Boulez brings Giuseppe di Giugno, a nuclear physicists, to IRCAM. Di Giugno was a researcher in the field of matter-antimatter in CERN and abandoned particle physics for research in electroacoustics and digital sound first working with Luciano Berio, and then with Pierre Boulez designing the 4 series.14

His work culminated with the 4x machine, the latest version of the 4 series which was used by Boulez in Répons. Di Giugno took the concept of speed and power in the domain of real-time DSP to a level that was not challenged for ten years. The 4x was a laboratory machine used by Boulez, Philippe Manoury and Robert Rowe to create small non-realtime works for tape, or for a combination of acoustic instruments and tape. (Wallraff 1979 )

The software needed to use such an advanced piece of hardware was not developed until the mid-1980, when Robert Rowe and Miller Puckette began working on a programming environment for such tasks. (MillePuckette 1986 )

Puckette in particular began using an early non-graphical version of Max to control the 4x that facilitated the writing of a real-time piece. Version of the 4 series included the 4A, 4B, 4C1, 4C2 and the 4X. From the 4A to the 4X there was an exponential increment on the processing power of the machine. The first one in the series could use 100 oscillators, the latter around 1000 and most importantly, it was capable of working in real-time. 15

4X Architecture

The system built around the 4X processor was based on a three-level architecture including host-control and signal processing systems. The first level consisted of several subsystems with a host computer (Mac, Pc or Unix) that serveed as a general development environment, a graphical user interface and a file server; the second level was used for real-time control of event handlers such as the control of MIDI controllers. The third level was the real-time signal processing system. The signal processor was a custom discrete design which could run programs as long as there were no jump instructions.\ The processor was particularly optimized for table lookup oscillators but was also capable of implementing other algorithms with additional programming. The 4X was controlled by a Motorola processor. 16 The disadvantage of using a three-level architecture was the need to create programs for each processor independently. These programs had to communicate reliably and some of the programs had to be written in a assembly, a low-level programming language, and only for integer processors which, although faster than floating point systems, could not handle complex code. (EricLindemann and Starkier 1991 )

The 4X and the MATRIX32

The 4x, a system used for real-time sound transformation, represents the fourth generation of a series of DSP processors for real-time applications developed at IRCAM. The first prototype was developed and built in 1980 by Giuseppe Di Giugno, with the help of Michel Antin. The last version was manufactured in 1984 by SOGITEC, a French company that manufactures technology for the military. Many 4x are being used today at IRCAM for analysis-resynthesis and transformation of sounds.\ The 4x used in Répons was a machine capable of processing 200 million operations per second (MOPS). It contained eight processor boards each of which could be independently programmed to store, manipulate and recall digitized sound waveforms. For example, it could process additive synthesis by adding 128 sinusoidal waveforms on each processor which could also be programmed to filter 128 different signals in real-time. The 4x was also capable of storing four seconds of sound that could be played back with a rhythmic pattern. The necessary operations for the manipulation and reproduction of the waveforms were encoded in modules that could be interconnected via its inputs and outputs. These modules could be programmed using a computer language written and implemented by Patrick Potacsek and Emmanuel Favreau. The interconnections between the modules were registered on a magnetic disk controlled by the Central Processing Unit (CPU) and could be accessed in less than half a second. The CPU run under a scheduling system capable of selecting a program and its time of execution. The system was developed by Miller Puckett, Michel Fingerhut and Robert Rowe. Each program could be loaded and executed in a fraction of a second allowing for a great flexibility during a musical performance.\ In addition to the 4x, IRCAM developed the MATRIX 32 that was used in Répons for the spatialization of sound in the concert hall. The Matrix 32 is basically a programmable audio-signal traffic controller, routing audio signals from the soloists to the 4X and from the 4X to the speakers. This machine was designed and developed by Michel Starkier and Didier Roncin.

On earlier versions of Répons, communication between the soloist and the 4x was based on a series of instructions programmed and stored on the machine's hard drive. This method, of course, required great precision and timing by the operator of the 4x in order to synchronize each individual soloist during the piece. Later versions of Répons required a different approach with a more direct method of communication between the soloists and the 4x.\ Another communication problem was specifically concerned with the acoustic signal generated by the performer. The sound from the instruments was analyzed and synthesized by the 4x in real time. For this to happen, the machine needs more information from the performer, something beyond the acoustic signal generated by the soloist, for example, something capable of transmitting pitch.\ After years of research and music technology development, this kind of communication was made possible by using the MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface) protocol. MIDI allows for the transmission of pitch, dynamics, durations, program change and other data. The protocol can be used to connect a keyboard with a MIDI output to a computer with a MIDI input. The protocol was welcomed by manufacturers of good quality instruments such as Yamaha, which created the Disklavier, a piano with MIDI capabilities.\ In Répons, the two pianos are equipped with MIDI and the 4x can receive and process data from the pianos to detect musical figures (trills, etc) and rhythmic patterns. The soloist can also change the connection between the modules, change a parameter of a module and send control messages from the soloist to the 4x, between soloists or from a soloist to the 4x's host.\

Analysis

Introduction

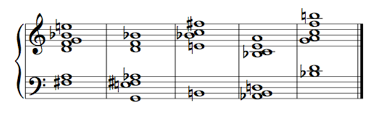

Boulez based much of the harmonic material in Répons on five chords, which are played in the first bar of the piece. The importance of these chords become apparent only by abstraction and analysis, since the speed with which they are played makes the perception of the chords as anything other than timbre. The real exposition of the chords occurs during the entrance of the soloists between rehearsal, figures 21 and 27. 17 Another important aspect of the work is the relationship between timbre and space. This relationship can be traced to Boulez's non-western influences. During his studies at the Paris Conservatoire in the 1940s, Boulez became aware of the musical traditions of Japan, Africa, Indonesia and India. This curiosity was stimulated by his composition teacher Olivier Messiaen, who introduced him to Balinese music. Messiaen had a theoretical interest in these musics. Messiaen was genuinely interested in the theory of rhythms from India, which he literally inserted into his music. Boulez instead was influenced by the sonorities and forms of other cultures, something that he could apply to his music without the visibility created by being artificially inserted. (Claude 1986 , p95)

Foe example, one of the sections in Répons was named Balinese by Boulez and Andrew Gerszo because the sonorities were similar to the fast and percussive style of a gamelan ensemble from Indonesia. (Jameux 1989 , p365)

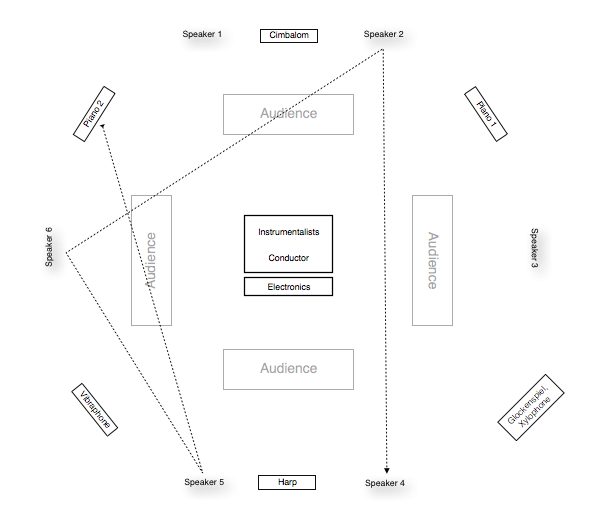

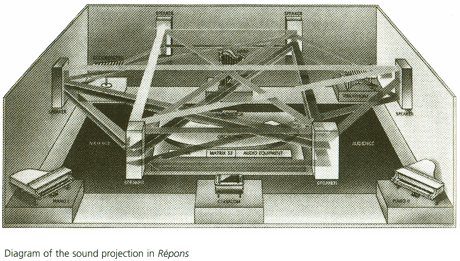

Répons is also concerned with the spatial relationship between the instrumental and the electroacoustic material. Therefore, realizing Boulez's ideas about audience, concert halls and loudspeakers, Répon requires a non-traditional hall or space for its execution. The audience sits between the instrumental ensemble and the soloists in a circular disposition. The speakers alternate between the soloists and are symmetrically positioned over the audience. Figure 1 shows the disposition of the instruments and speakers and the spatial orbits of Piano 2 at its entry in the beginning of section 1:

There is also a concern with isomorphism and difference that is exposed by the contrasting timbres perceived in every section of the piece. These differences in textures are a structural element of the form. 18

Boulez's notion of a three-dimensional arpeggio moving across from the soloist' responses to the electronic echoes, all derived from transformations of the same chord, displays a concern with isomorphism and difference, with obtaining something syntactically related yet distinct, which goes back to the problems he tried to solve with the serial proliferation of the Third Piano Sonata. (Williams 1994 , p198)

In System and Idea, Boulez outlines a series of techniques for articulating the relationships between the macrostructure and the microstructure by using the concept of 'constellations'. (Boulez 1986 )

The first of these techniques relates to the use of polar or anchor notes and their influence on the surrounding pitches creating a gravitational system that revolves around a central pitch. For example, a type of constellation found in the soloists writing, is the long trills, which attract auxiliary notes. Other constellations include the dense vertical harmonies with envelopes (resonances) and transformation of blocks by external elements. \"An aura of adjacent phenomena is formed in basically two ways in Répons: as an extended anacrusis-type figure or as a chord around a sustained , other thrilled, sonority". (Williams 1994 , p201)

The instrumental forces are the following: an instrumental ensemble of twenty-four players: two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, bass clarinet, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, two trombones, tuba, three violins, two violas, two cellos and a double bass. This ensemble is acoustic; there is no amplification or processing. The “resonant grou” which comprises the soloists placed symmetrically in a hexagonal shape. The solo instruments are two pianos (I and II), piano 2 doubling a DX7 synthesizer; harp, cimbalon, xylophone (doubling glockenspiel), and vibraphone. The latter group is amplified by microphones placed closed to each instrument and their sounds can be processed and spatialized in real time by the 4X and the MATRIX32 respectively.\ In Répons there are pre-recorded sounds that can be activated by the soloists. These sounds are something that Boulez calls "continuous wallpaper music" and only becomes audible when the soloist exceeds a certain dynamic; there are small speakers above each soloist for this purpose. (Jameux 1989 , p359)

It is clear by the disposition of the ensemble, the audience and the soloists that Boulez was trying to recreate a digital responsory; the main purpose of the electronics is to disseminate the music of the soloists throughout the speaker system. The electronic transformations used in Répons can be divided into three categories:

-

The spatialization of sound that can create a perception of circular movement giving the impression of continuum movement or create its own responsorial path, with or without transformation. 19

-

The transformation of a solo instrument by a synthetic sound. For this purpose, Boulez uses ring modulation synthesis. 20 This process enriches the timbre of the sound by creating two sidebands on the resultant signal. These sidebands are the sum and the difference of the frequencies particular to the two initial sounds. (Boulez 1992 , p45)

-

Time shifts: including echoes, delays, and phase displacement that can create rhythmically complex motifs or can be projected as a spatialized echo. Delays are notably present on the entry of the soloist and the coda. Of course these methods are a form of response to an initial sound. In addition to the electroacoustic realization of these effects, Boulez creates instrumental delays with staccato repetitions of the same note, notably by the brass section during the introduction.\

It is difficult to describe the sonorities, considering the spectral changes of sound when is spatialized, by listening to a recording. Nevertheless, Boulez uses the same criteria for both instrumental and electroacoustic writing:

Répons is a work which rest entirely on the responsorial relationship between instrumental sounds and their electroacoustic transformation -- a relationship that is, moreover, extraordinarily complex and problematic to its production. But like the methods applied to the instrumental writing, the transformations themselves are very simply defined, sharply contrasted, and almost transparently clear. (Jameux 1989 , p364)

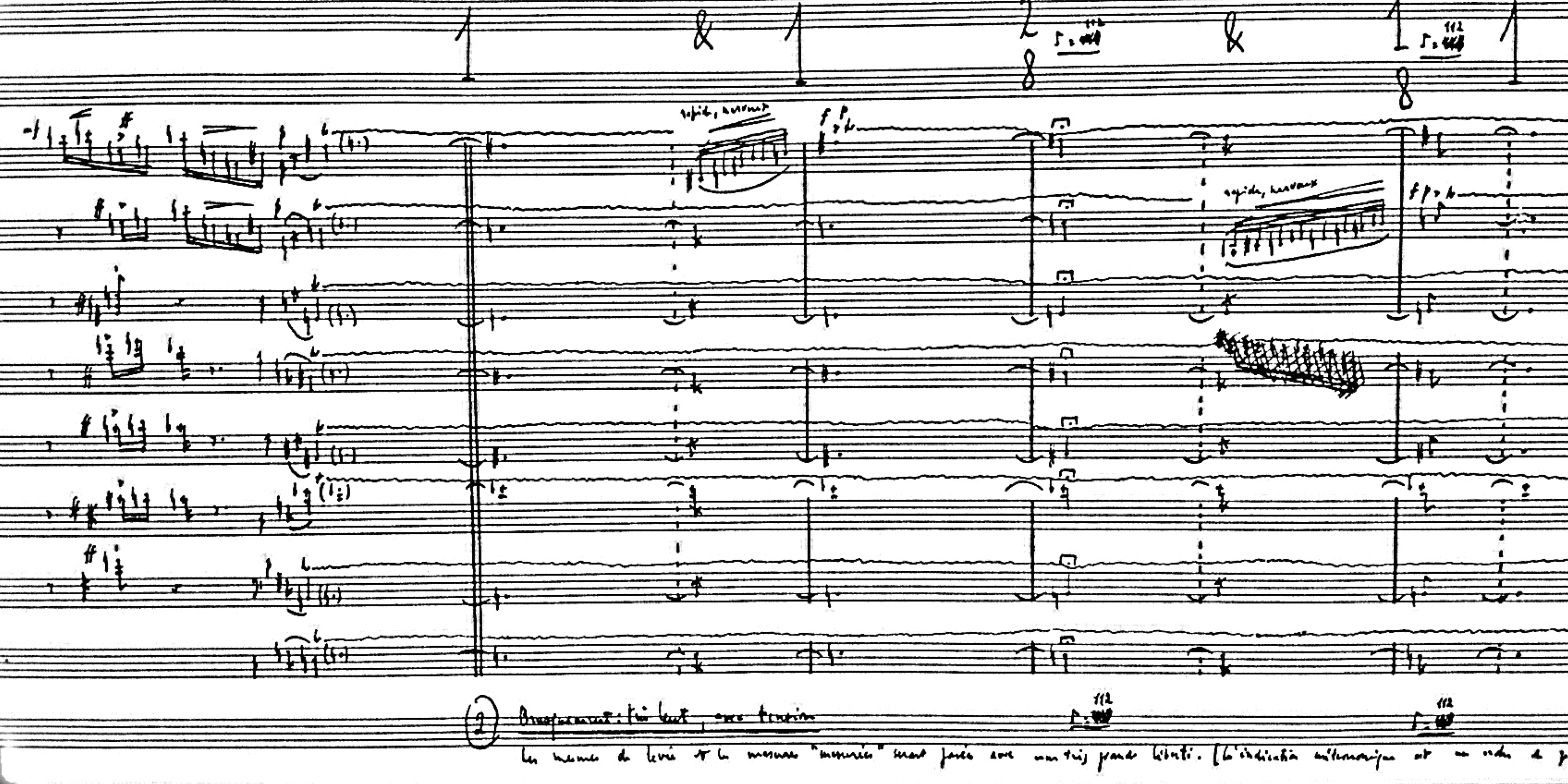

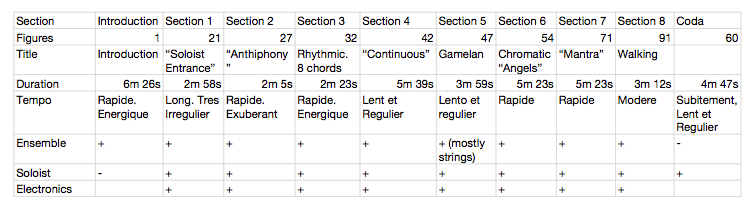

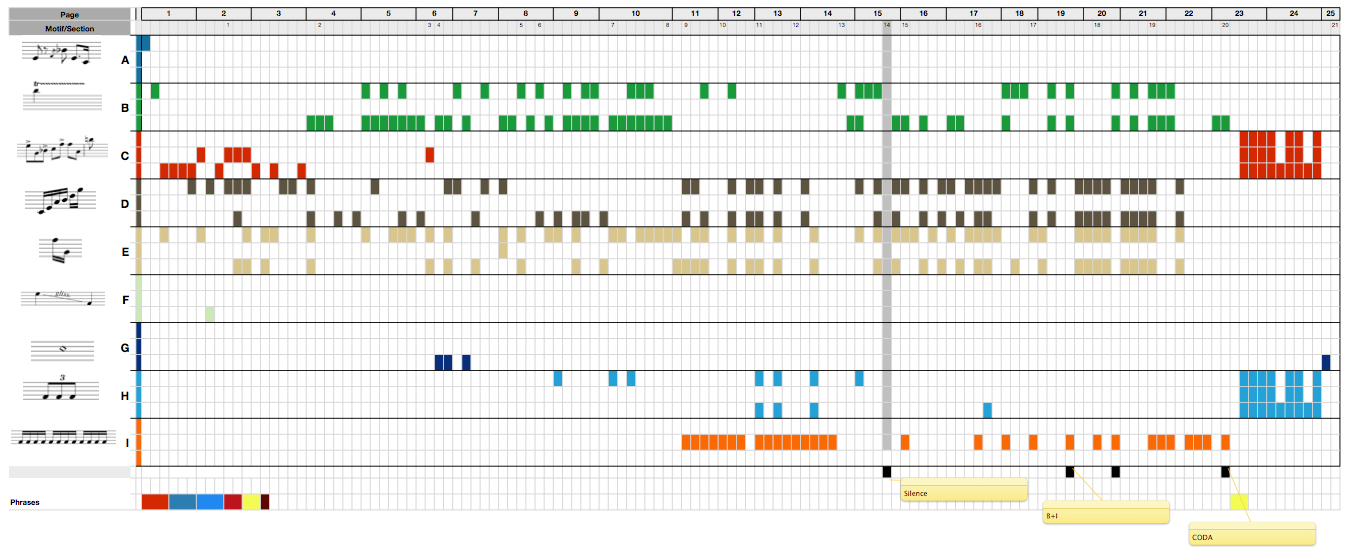

Introduction

Répons consists of an Introduction, followed by 8 sections and a Coda. Each section presents different combinations of instrumental forces and different electroacoustic and spatialization techniques. The instrumental introduction, from the beginning to figure 21 with a duration of approximately 6:26 is marked rapide, energique. It begins with a syncopated staccato style with a degree of homophony between the three groups of woodwinds, brass, and strings. Around 30 seconds into the section, a string trill preceded by a fast rising arpeggio is answered a measure later by a two note fast descending gesture of larger intervals.\ This idea provides a background to the rise and fall of woodwind figures and what will become the central material for the entire piece.

The passage is sharply punctuated by the brass. At around 3:30, a unison brass creates its own "responsorial" delay by using repetitive staccato gestures that develop into a tutti that comes to a halt at figure 20, where a small coda begins leading to section I. There are no pauses between sections in Répons.

Section I

During the Introduction, the soloists stand silent and in darkness in each corner of the hall. This adds to the tension created by the long trills played by the strings. At the beginning of Section,1 Long, tres irregulier, the stage is suddenly illuminated revealing the soloists. The lights are synchronized with the music. 21 The soloist entrance, from figure 21 to figure 27 (dur. 2:58), produces a deep psychological effect on the audience. The contrast between the sections is mostly provided by the change in timbre. The solists, the electroacoustic material and the spatialization creates the impression of a large resonant space and a sense of continuity only hinted at by the long trills in the strings during the Introduction.

By watching a live performance of the piece, one realizes the theatrical aspect of it, which Boulez of course had intended. In this section the soloists expand and transform the main idea presented during the Introduction with the aid of the 4X. The resonant instruments play six arpeggiated chords which are sustained, amplified and spatialized by the electronics throughout the entire section. At this point, all the material for Répons has been introduced. 22

Section II

ÒAntyphony between the soloists and the instrumental group is particularly spectacular during a section from figure 27 to figure 32, in which the soloists are placed under the regime of the delay system. In this section marked Rapide, exuberant there is delay and spatialization of the gestures. The Répons is found between the instrumental group and the soloists. There is a total of 5 antiphonies. In addition, the writing for the soloists shows a temporal expansion of the arpeggios of Section I, which were derived from the rising arpeggios of the Introduction. (Jameux 1989 , p365)

Section III

Marked Rapide, energique, this section spanning from figure 32 to 42, was called the "Balinese" section by Boulez and Andrew Gerszo because it resembled the fast, percussive style of the Gamelan. (Jameux 1989 , p365) Throughout the section, the soloists provide eight resonant chords that are preceded by the similar uprising gesture of the previous sections. This time, the arpeggiated gesture combines upward and downward movement spanning the range of several octaves, most notably in the pianos. These 8 chords serve as an accompaniment to the ensemble which mostly plays fast 16th note figures consisting of small intervals with no rests.

Section IV

From figure 42 to 47, this section bring the arpeggios by the soloist to a climatic development. The arpeggios are connected by long trills creating a continuity of sound achieved before by the use of electronics. The ensemble punctuates with sporadic arpeggiated gestures and long sustained notes that belong to a second listening plane.

Section V

From 47 to 53, this section indeed resembles a Gamelan. This time the resonant instruments of the soloists, which are all the percussion instruments, reveal their nature by playing fast passages with a staccato "dry" sound. Several electronic transformations are heard throughout the section and there is a clear contrasting timbre regarding the use of space and resonance. Toward the end of the section, the electronic transformations are part of the foremost listening plane with the classic sound of ring modulation.

Section VI,VII,VIII

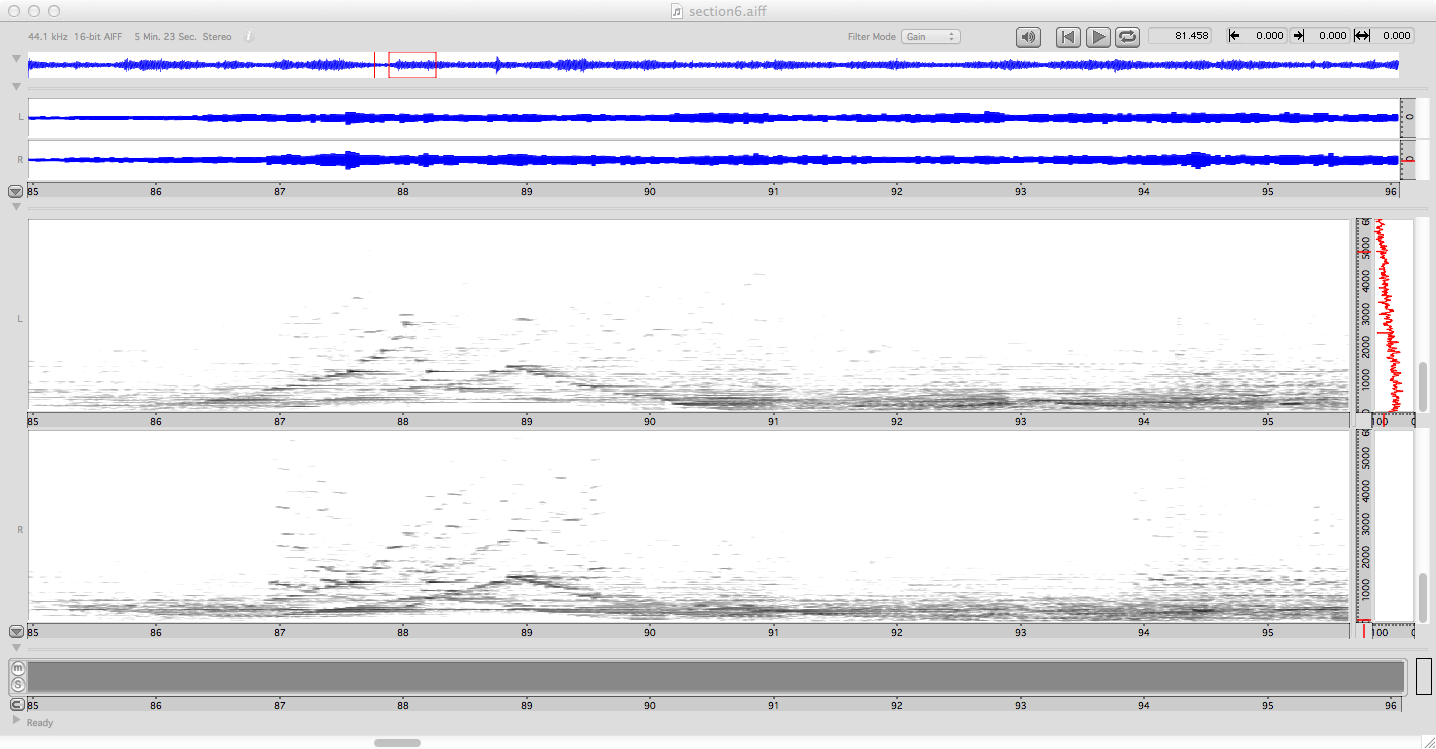

Given its texture, section VI completely saturates the space and the score. There are three clear sections from figures 54 to 59, which are similar in nature. This similarity comes from the combination of fast ascending and descending chromatic notes, which are the result of a developmental treatment of the previous arpeggiated gestures and fast repetitive notes played by the soloists. Let us remember that these gestures were a development of the repetitive notes on the brass during the Introduction. The dense texture relentlessly fills the space for around 7 minutes. 23

The passage from the beginning of section VII where the ring modulated piano is more present, resembles Stockhausen's Mantra (1970). A sudden signal by the brass marks the ending of the chromatic writing in the middle of section VII (figure 80). 24 This gesture is answered by the ensemble with the "delay" technique. The brass signals again before figure 82 when we hear the original rising arpeggio by the strings followed by the woodwinds. Right before figure 84 marked Rapide, we hear for the first time something that resembles the syncopated motif of the first measures of the piece.

Towards the end of section VII the motif played by the ensemble is expanded and "disintegrates" at figure 90 with a halt that marks the beginning of section VIII. The piano plays a "walking bass" pattern with a discernible steady pulse. This pattern and its respective answers by the ensemble are a development of the first measures of the piece.

Coda

As a response to the Introduction for the ensemble alone, the last section of Répons is entrusted to the soloist and electronic transformations. The writing comprises of appearances of the arpeggiated chords that are transformed with different techniques. The sounds are clear without the wash of delays, mostly on the foreground of the listening plane. The tempo is slower contrasting the previous sections of the piece. Towards the end, there is more space between the gestures, ending with an arpeggiated chord played by Piano 2.

Harmonic Structures

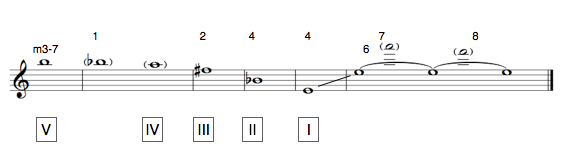

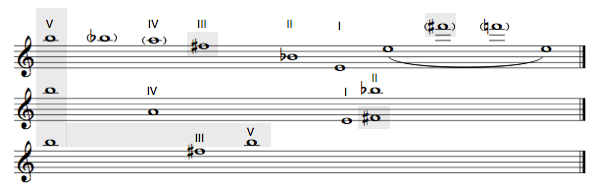

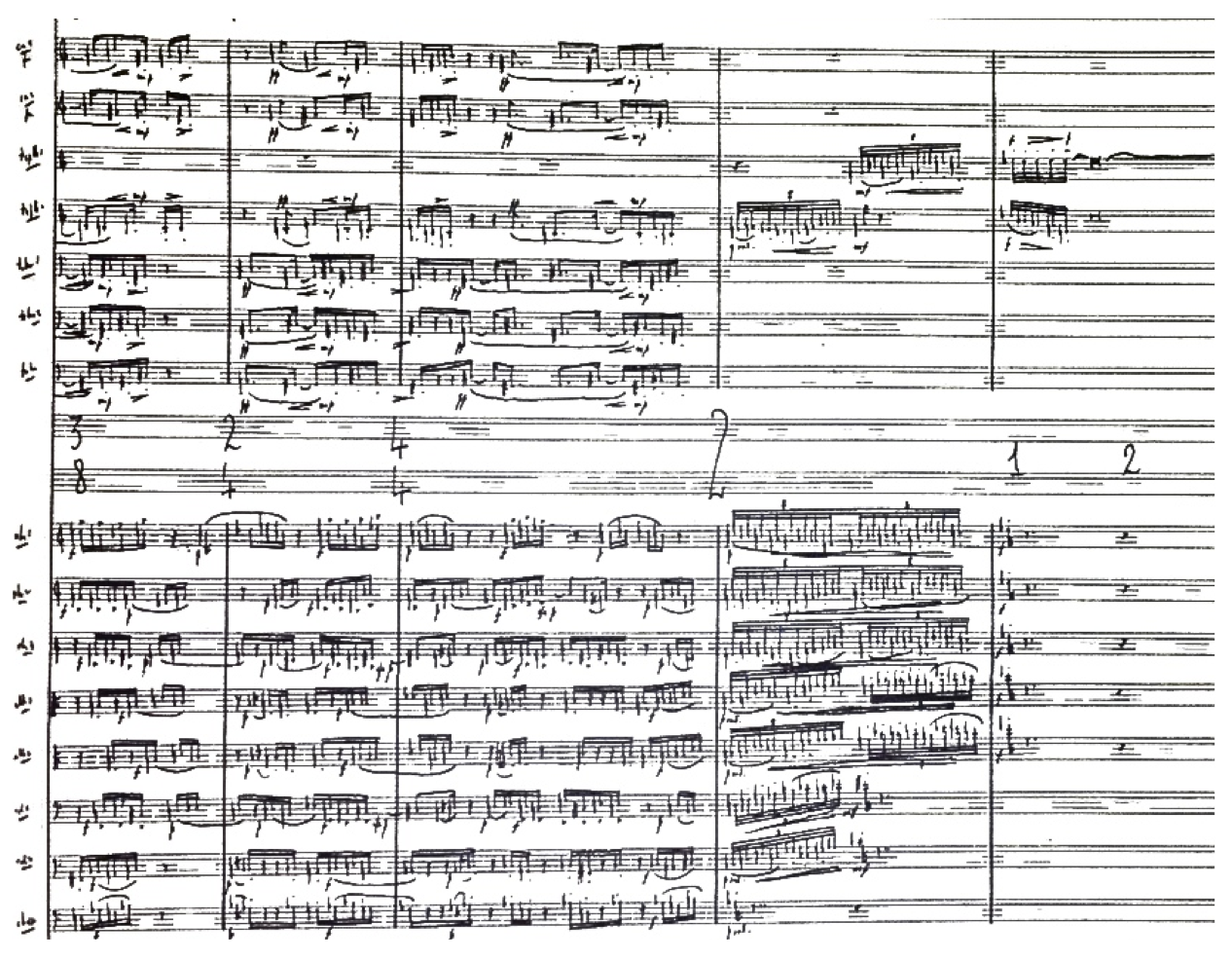

During the Introduction, Boulez lays out the harmonic structure of the piece with 5 chords. To build these chords, Boulez uses a winnowing technique, departing from total chromaticism. Seven notes are screened creating a chord that contains the presence of stacked thirds without suggesting a tonal center. This particular diatonic universe brings to life a solid harmonic structure for the entire piece. These chords are presented during the first measure and first beat of the second measure of the piece.\

Starting on measure 3, a gesture with a predominant B played by the flute is closed on measure 7 by a fast inflexion by the ensemble. B is the top note of the fifth chord of the harmonic exposition. This type of gesture is very common in Boulez's music. (Boulez et al. 2006 )

There is also a Bb that can be heard during three measures, between 3 and 5. It seems that an A is the predominant note. That A is the top note of the fourth chord of the harmonic exposition. What follows is an F# , the top note of the third chord, heard between measures 7 and 10.\ The first violins play and sustain the note for a long time starting on figure 2. At figure 2, the Bb from the second chord of the exposition returns to the flute. At the fourth measure of figure 4, the E of the first chord in the harmonic exposition is played by the violins. Later, it appears in a different register (at figure 6) and is embellished by an F# and F from measure 6 to 8.\ Concluding, during the first eight figures of the piece, we can hear a melodic line that is derived from the top notes of the harmonic exposition.

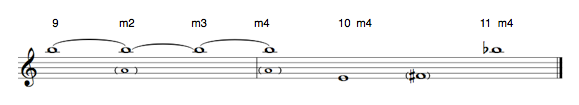

From figure 9, the melodic line starts in reversed order. At measures 2 and 4 (of figure 9), the A reappears as the dominant note. The F# almost disappears and is transferred to the violas at figure 10. At measure 4 of the same figure, the E of the first chord appears and is followed by a Bb at figure 11, measure 4.

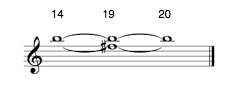

From figures 14 to 20 there is a predominance of B with an F# at 19.

A melodic curve during the Introduction is derived from the 5 first chords of Répons. The prevalence of B, and F# is still evident, but to a lesser degree.

This is corroborated by a spectral analysis of the Introduction showing higher energy around B and F#, as shown in Figure 7. 25

Moreover, a logarithmic spectrum of the entire work shows energy with peaks around B.

Tempo and Meter

In Répons, strict and more flexible tempo marks alternate, creating a balanced work. The sections marked rapide. energique seem to be more strict than the slow sections. The length of the slow sections added together is around 20 minutes, half of the duration of the piece. Although slow sections are mostly marked lent et regulier, their flexibility is given by the constant alternations of accelerandi and ralenti. There are different temporal levels given by the alternations of tempi with measured and unmeasured moments, especially in the sections marked lent. The last level being the fluctuations in the pulse such as in the accelerando and ritardando passages. The metric fluctuations are intrinsically related to the rhythmic figures (See figure 12). This is clearly seen in section 6 where the fast chromatic passages were written using 32nd note figures. This flexibility found in Répons can only be possible by the use of real-time electronics, (4x) which make the piece more organic compared to electroacoustic works written for fixed media. Célestine Deliège compares rhythm and meter to the relationship between the lungs and heart of a living organism governed by an internal rhythm. (Deliege 1988 , p57) During the Introduction, a syncopated and non-regular rhythm can be perceived until the figures on the brass punctuate a fast pulse that helps the listener to internally contextualize the long trills heard before. When the brass stops playing those figures, a rhythmically "chaotic" coda emerges before the entrance of the soloists. In section 6 ("angels')', the steady repeated notes of the soloists provide a layer for the ensemble, which play fast chromatic ascending/descending gestures. The combination of a fast rhythm, the continuous chromatic notes, the support of the electronic transformation of the soloists and the spatialization, perhaps imprints the listener's perception with images of angels flying around the performance space. 26

Spatialization and Theater

Boulez's remarks on the connection between theater and his music provide an insight of a greater idea behind Répons. In addition to being a landmark in the history of electronic music, the seminal work incorporates a new element to contemporary music: spatialization.\ The concept of spatialized sound is not new for the audience who is familiar with theater and/or opera as in the latter, for example, the performers sing while moving around the stage. There are few concert pieces that ask performers to do such a thing. Perhaps the most relevant example is Eonta' (1963-64) by Iannis Xenakis where the brass ensemble moves to different parts of the stage during the performance. The players also move their instruments from left to right in an oscillatory motion. In addition to the visual aspect of the performance, the oscillatory movement provides spectral changes as a result of the acoustics of the hall. This is, of course, well intended by Xenakis who also asks the performers to blow their instruments inside the piano making its strings vibrate as they play. In Eonta, Xenakis achieves what Boulez intends in Répons by combining a theatrical performance, the use of spatialization and timbral transformations. Xenakis, as a composer and architect, knew very well the possibilities of the unique spectral modulations provided by the different shapes of concert halls. Boulez mentions his interests for theater in an interview with Rocco DiPietro:

I'm also very interested in the tradition of Japanese theater, like the Noh and Bunraku, which I find extremely interesting. In fact, I would like to renovate the theater in this direction. I tried to do that with my work Répons, which cannot be performed in a conventional concert hall because of the setting. I would also very much like to change the relationship between instruments and voices in opera using technology to try to have an equivalent of masks in sound. By that I mean I would have voices with a sound mask and instruments with a sound mask through the processing of computers. I could, in fact, have quite a lot of things, which are difficult to realize in a conventional opera house...in Répons, I had the orchestra in the center, the audience with loudspeakers and all of the sound coming from the instruments completely transformed by technology. (DiPietro 2001 , p60)

Spiral Forms

Boulez mentions Proust several times, and like the French novelist he does not want any breaks in the music. Ideas can be introduced and abandoned as part of one monumental work. This is seen in most of Boulez's pieces, which he considers works in progress, always contemplating the idea of the infinite.\

As for Répons, where I progressively added elements, you are in the midst of a spiral form...I'm fond of this type of form that is infinite, with its double meaning, which can be extended infinitely. (DiPietro 2001 , p69)

Responsorial

Répons is a French medieval musical term for antiphonal choral music, or a soloist and a choir that responds to the soloist. 27 Pierre Boulez applies the concept to different levels throughout his work. In Répons there are many different sorts of dialogues, for example: between the soloists and the ensemble, between the soloists, and between the passages of music and their transformations by the 4x.

All musical aspects are part of the responsoriale: pitch, rhythm, temporal organization (form), dynamics and timbre. The real-time transformations provided by the 4x are also part of the dialogues; each solo instrument is equipped with a microphone. It is possible then to transform the acoustic signal of each soloist and spatialize it around the audience in the hall.

Traditional responsorial form consists of two ideas, the first one is the placement of the voices (choir) in space: choir and soloist are located in different parts of the church. The composer does the same in Répons by placing the chamber ensemble in the center of the performance hall and the soloist around the audience; the audience sits between the two.

This displacement can be understood as a general transformation on any dimension of the music, for example if we consider frequency a musical dimension, the displacement would be to modify the frequency such as a transposition of a melody to different keys. At the temporal level, this displacement is achieved by removing or adding components to the sound spectrum. The second idea in antiphonal music is the response itself. A number of voices (choir) respond to one voice (soloist). At a different level, a single note or single chord in Répons can create numerous notes or chords that resemble their originals.

Bach

The realization of Répons was possible by the invention of a machine capable of replicating and proliferating the original material in real time, allowing the composer to make his various choices as he goes along. It can also be used directly in a performance, thus creating a dialogue between traditional instruments and electronic devices, freeing the performers from dependence on tapes (Davidosvsky's Synchronisms).

The 4x is in fact a new instrument capable of reproducing musical material that satisfies the demands of an imagination thanks to an institution that made it possible to invent, create and make the machine available for concerts (as a traveling instrument). This was Boulez's alliance between material and invention, an idea that occurred to him around 1951 when reflecting on two Bach's chorales. (Boulez 1966 , p22)

Boulez also brings back images of his childhood in his piece Anthèmes II (1998, dur. 20 minutes), which is a revised and electronically expanded version of the eight minute long Anthèmes I (1991) where he recalls the verses of Jeremiah Lamentations using long harmonic notes:\

I remember when as a child we used to chant the Lamentations of Jeremiah during Easter holy week. What struck me then was that although the text was of course in Latin, the verses were separated by letters, that were themselves chanted, but in Hebrew; that is, aleph, beit, etc. This is close to the system I have used here. After a short introduction, the first letter, announcing the first paragraph. This is followed by the paragraph, in which there is a certain amount of activity. This stops and is followed by the second letter, then the second paragraph, etc. The form of the piece is entirely deduced from this. (Goldman 2001 , p40)

As in Répons, Boulez makes reference to something religious, but in Anthèmes, the references are textual. This is a fascination that Boulez inherited from Mallarmé, and provides an intellectual framework for his biblical interpretations. In Répons the reference goes beyond the title of the piece: the orchestration and electronic realization of the work recreates both the responsorial and the physical space of the church in which the chants are performed. The following are the two chorales Boulez makes reference to:

Chorales

-

The three part imitative accompaniment in the pedal and lower keyboard of this chorale prelude is based on figures derived from the 4 different lines of the melody and their inversions; each line of the cantus firmus itself is heard in the simple soprano line, striped of any embellishment, after pre-imitation in the ritornello parts.\

-

\ A set of five variations in canon on a Christmas chorale for organ.

The movement is a Fughetta, for the manuals, on the first two phrases of the melody. In more vivid colours Bach paints again the Orgelbuchlein picture. The brilliant scale passages not only represent the ascending and descending angels, but sound joyous peals from many belfries ringing in the Saviour's birth. 28

The above description of Bach's chorale can also be used to depict section 6 of Répons, where the orchestration and instrumental writing invites the listener to recall the same image of angels and bells. This time, the angels are the fast chromatic passages in the ensemble and the bells are the long notes in the brass. The electronic transformations and the fast notes played by the soloists add to the atmosphere, creating a multidimensional sound space.

Envelope Follower and Spatialization

Répons begins with the instrumental ensemble. The electronic transformations and soloists join the ensemble later during the first section in the following order: cimbalom (soloist 1), Yamaha Disklavier (soloist 2), xylophone and glockenspiel (soloist 3), harp (soloist 4), vibraphone (soloist 5), Yamaha Disklavier and synthesizer Yamaha DX7 (soloist 6). The entrance of the soloists features a short arpeggio that "resonates" in the concert hall for eight seconds until the sound almost disappears. This first gesture is used by the 4X and the MATRIX 32 by spatializing the arpeggio's tail using the six speakers located around the audience. Sound spatialization in Répons is not limited to diffusion of sound (as in surround techniques widely spread in cinema). The composer approaches spatialization from a different perspective. By slicing an envelope follower into 6 different parts and synchronizing each chunk, the 4X can spatialize sound according to dynamics and pitch. With this technique, sound is broken into smaller elements.\ These elements can be emphasized or reduced, and can be located in space or can travel in circular motion around the audience creating an illusion of displacement. Because Répons uses envelope followers to spatialize sound, greater dynamics translate into a faster circular motion of the sound around the audience while softer dynamics can result in the sound being perceived as static.\

Temporal Expansion of Arpeggios and Pitch

For each spatialized arpeggio, the conductor gives a signal at regular intervals to each soloist, who afterwards plays another arpeggiated chord. These successive arpeggios become one entity. Five of those chords are sent and stored in the 4X, which can make 14 copies of the original sound giving each copy a different delay time. Each copy is modified and replayed. This represents the arpeggio of an arpeggio of an arpeggio, etc. which adds meaning to the form of the piece and expands the concept of the arpeggio ,translating the instrumental writing to electronic music.\ Pitch transposition is achieved by applying the same concept of translation from instrumental writing to writing for electronics. In Répons, chords are derived by transposition of pitches from other chords. Most of the material in Répons is derived from five chords, which are the first 5 chords in the first measure of the Introduction. Chords are divided into smaller parts that travel to create new chords, creating a harmonic transformation that translates into a spectral spatialization.\ Moreover, the transformations are limited to dividing the chords into two smaller chords, which then become the top or the bottom of a new chord that is transposed an octave up or down depending on the orchestration. The same approach is applied by the 4X. Fourteen copies of a sound (chord) are independently transposed, keeping some notes at different octaves thus changing harmonic color. This can be interpreted as a transposition of a transposition. The modules do not preserve the harmonic structure of the sound; in order to achieve something like this, it would be necessary to use a computer with a more powerful processor and capable of analyzing spectra. For example, a system capable of doing an FFT in real time. 29

Signals

One of the most basic qualities of a sound is its capability to act as a messenger. A sound can become an acoustic sign that can indicate for example, a storm, in the case of thunder. Then a sound can mark an event, a break or change. A sign can be an isolated note, a motif, a gesture, or a series of repetitive notes such in the case of Répons' section VII, where the repetitive notes of the trumpet indicate a new figure, which brings an element of change to the score. At figure 90, section VII, we see a change in texture signaled by the brass.

The signal belongs to a temporal context and break with the continuity of a passage. Signals are of a punctual order, envelopes are of a global character. (Boulez 1986 , p49)

Boulez emphasizes the immobility of the signal: it marks an important event or anticipates change without linking it to time as with the envelopes. Signals are static elements that do not anticipate any future developments: they break continuity. In Répons signals take a multitude of forms, for example, long high notes or a particular electronic transformation. "It [a signal] is generally characterized by a sudden simplification of the texture (a drop in intensity, rhythmic speed, dynamic intensity, etc)". (Goldman 2011 , p67)

Conclusion

Répons translates Pierre Boulez's interest in the process found in some medieval music. The title for the work makes a direct reference to the alternation of a chant from a soloist and a choir during a church service. All the elements of the work are carefully planned in order to present a theatrical experience to the audience. These elements include the disposition of the audience, the ensemble, the soloists and the speakers. The composition of the piece and the aid of the electronic transformations make a clear reference to the echoes heard during a responsorial chant.\ As in Bach's "Von Himmel hoch", the writing evokes what a devotee would find in a cathedral during service: a fresco depicting flying angels. As with the Renaissance painter Giotto whose paintings of angels seem to be animated, in Répons the angels are not static; they fly around the audience accompanying the responsorial. This was possible with a ground-breaking achievement by the composer as the director of IRCAM: the 4x. Moreover, Boulez breaks with several traditions that are centuries apart, firstly transforming the concert hall from a static framework for the composer into a multi dimensional and dynamic space, and secondly, by freeing performers from the tyranny of the tape recorder.

Appendix A. Studio Equipment Found in the studios of Milan, France and Cologne

Sound Generators

-

Sine and sawtooth waveforms oscillators 30.

-

White noise generator

-

pulse generator

Filters and Analysis

-

Chamber, tape, and plate reverberation units

-

Octave filter

-

High-pass filter (6 cutoff frequencies)

-

Low-pass filter (6 cutoff frequencies)

-

Variable band-pass filter

-

Third-octave filter

-

Spectrum Analyzer

-

Ring and amplitude modulators

-

Variable-speed tape machine

-

Springer time regulator (variable-speed tape recorder 31

-

Amplitude filter

Recording and Reproduction Equipment

-

Microphones

-

Mixing console

-

Amplifiers and Loudspeakers for four-channel sound monitoring

-

monophonic tape recorders

-

two-channel tape recorders

-

four-channel tape recorders 32

Appendix B (Timelines)

Timelines

Notes

-

Without seeing or knowing the conventions of an art -- if these conventions are evident to the eye and produce good results, we admit them and accept this means of expression: this is universally true of all means of expression ↩

-

The vineyard style is a term used for the design of a concert hall where the seating surrounds the stage, rising up in serried rows in the manner of the sloping terraces of a vineyard. ↩

-

Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique, originally conceived as a Max Planck Institute but the idea was rejected by Werner Heisenberg who could not see contemporary music as a proper concert of the august German body (Schroeder,322) and/or economic reasons (Jameux,168) ↩

-

IRCAM has to be autonomous as opposed to the facilities offered by radio stations or universities where researchers are absorbed by pedagogical tasks ↩

-

Davidovsky established himself internationally as a pioneer in electroacoustic music with his Synchronisms for a variety of instruments and tape. These pieces require the performer to synchronize with pre-recorded material on tape. ↩

-

And was also justified by several writings including Present and Future - A fundamental Requestioning, La musique en project, Gallimard/IRCAM, 1975 and Technology and the Composer, The Times Literary Supplement, 6 May 1977. ↩

-

Groupe de Recherches de Musique Concrete (GRMC) was established in 1951 and to this day is a laboratory for experimental sound. After 1958 focused on the creation and research in the field of electroacoustic music. (GRM) ↩

-

See Appendix A ↩

-

Real Time Electronics is the technique of transforming sound electronically and projecting it thorough an array of speakers allowing for a direct interaction between performers and machines during a performance. As opposed to synchronized tape music, real-time electronics frees the musicians from the fixed and inexorable rhythm of pre-recorded material. ↩

-

www.cycling74.com ↩

-

http://www.crca.ucsd.edu/ msp/software.html ↩

-

Other software includes AudioSculpt, Modalys, OpenMusic, Flux, IRCAM Tools, and various plugins. ↩

-

Ongoing research at IRCAM can be found here: http://www.IRCAM.fr/60.html?L=1 ↩

-

One of the first programmable real-time DSP machines designed specifically for musical applications was the DMX-1000 created by Dean Wallraff in the late 1970s. Around the same time a group at Stanford was working on the Samson Box and Jean-Francois Allouis was developing the SYTER at GRM. In Holland, in 1980, the Institute of Sonology of Utrecht had the DEC PDP-15. Other companies including Farilight and New England Digital were starting to build programmable machines. Most of the programming was done in FORTRAN, C or Assembly (Wallraff 1979 ). ↩

-

The original non-graphical version of Max (Max/MSP) (Puckette 1988 ) ↩

-

The 4X was controlled by a VME- based Motorola MC78000 running a proprietary kernel that could be programmed using a Sun Microsystems workstation and compiled using a dedicated signal processing compiler developed at IRCAM (EricLindemann and Starkier 1991 ) ↩

-

See figure 3 ↩

-

Gestalt psychology of perception ↩

-

See section 5.4 Spiral Forms ↩

-

Ring modulation (RM), a special type of amplitude modulation (AM), is obtained by multiplying two bipolar signals, a carrier (C) and a modulator (M). In the case of Répons the carrier is the signal captured by the microphones placed on each soloist. The modulator is a simple sinusoidal wave ↩

-

See section 5.3 ↩

-

The same is true for the ending of the performance executed only by the soloists leaving the ensemble in darkness. An excerpt of the DVD Pierre Boulez: Inheriting The Future of Music can be watched here: http://youtu.be/pF-F6-VFCWM . Last accessed 01/04/2012. ↩

-

See section 5.6.1. Figure 3 ↩

-

See Boulez's signals. Section 5.9 ↩

-

A logarithmic spectrum showing a Meter scale with an FFT window size of 4096 and 25% overlapping ↩

-

See section 5.7.1 "Chorales". ↩

-

Christian responsorial chant ↩

-

Charles Sanford Terry. Bach's Chorales. Vol. 3, 1921. ↩

-

Fast Fourier Transform is an algorithm that decomposes sound into its spectral components. As with any transform, it converts time-domain signals into their spectral-domain counterparts. ↩

-

Some of the equipment is cataloged in Repertoire des musiques experimentales Paris, GRM,1962 ↩

-

Springer tape machine with rotating heads for suspending sound. An ancestor of the rotating heads used in video machines ↩

-

In cologne, among the first anywhere in the world ↩

Bibliography

Rowe Mille Puckette, editor. Software Developments for the 4X Real-time System, IRCAM, International Computer Music Association, 1986. ↩

Miller Puckette, editor. The Patcher, International Computer Music Association, 1988. ↩

Pierre Boulez. Relevés d'apprenti,. Éditions du Seuil, Paris, 1966. ↩

Pierre Boulez. Le système et l'idée. Harmoniques: le temps de mutations, 1(1):49, Dec 1986. ↩ 1 2

Pierre Boulez. Orientations: collected writings. Faber, London, 1986. ISBN 057113811X. ↩ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

Pierre Boulez. Repons. Universal Edition, 1992. ↩

Pierre Boulez. Boulez: repons. dialogues de l'ombre double. CD. IRCAM, Centre Georges Pompidou, 1998. ↩

Pierre Boulez, Frank Scheffer, Andy Sommer, Hélène Jarry, Ed Spanjaard, Joël Bons, Frank Scheffer, Nieuw Ensemble, Ensemble intercontemporain, Idéale Audience International, Allegri Film, AVRO (Firm), Cinquième (Firm), and Mezzo (Television station : Paris, France). Pierre boulez eclat ; sur incises. 2006. ↩

Samuel Claude. Eclat/Boulez, Repons de Pierre Boulez. Editions du Centre Pompidou, 1986. ↩

Celestine Deliege. Moment de Pierre Boulez, sur l'introduction orchestrale de Repons. IRCAM, 1988. ↩

Rocco Di Pietro. Dialogues with Boulez. Scarecrow Press, Lanham, Md, 2001. ISBN 0810839326. ↩ 1 2 3

Bennett Smith Eric Lindemann, Francois Dechelle and Michael Starkier. The architecture of ircam musical workstation. Computer Music Journal, 15(3):41–49, Autumn 1991. ↩ 1 2

Jonathan Goldman. Understanding pierre boulezís anthËmes [1991]: ëcreating a labyrinth out of another labyrinthí. 2001. ↩

Jonathan Goldman. The Musical Language of Pierre Boulez. Cambridge University Press, 2011. ↩ 1 2 3

Dominique Jameux. Pierre Boulez. Faber an Faber, London, 1989. ISBN 057113744X. ↩ 1 2 3 4 5 6

Dean Wallraff. The dmx-1000 signal processing computer. Computer Music Journal, 3(4):44–49, Dec 1979. ↩ 1 2

Alastair Williams. 'Repons': Phantasmagoria or the articulation of space? Cambridge University Press, 1994. ↩ 1 2