Abstract

Current philosophical thought in Object-Oriented Ontology is applied to sound spatialization aiming at clarifying the interaction between the listener and moving sound sources in sound fields. The author discusses the sound object and sound hyperobjects considering their spectromorphology in correlation with time as an essential aspect of music.

Introduction

In our era of digital saturation, we consume and discard media at an unprecedented pace. Yet, our auditory perception remains remarkably acute. A trained ear can distinguish between a Beethoven and a Mozart sonata in a fraction of a second, much like how we instantly recognize a friend's voice on the phone. This rapid recognition stems from our evolutionary ability to extract crucial information from sound for survival.

The key to this swift identification lies in timbre, scientifically known as spectra. Timbre is the unique “fingerprint” of a sound, encompassing its harmonic content, attack-decay characteristics, and texture. A mere second of audio can reveal a wealth of information: the composer's identity, instrumentation, historical period, as well as specific musical elements like harmony, melody, pitch, duration, and dynamics.

Consider timbre as the DNA of sound. Just as a small DNA sample can identify an individual and provide insights into their genetic makeup, a brief audio snippet can unravel the complex tapestry of a musical piece. This auditory DNA allows us to rapidly process and categorize sounds, demonstrating the remarkable efficiency of our auditory system in decoding the rich information embedded in timbre.

This analogy extends our understanding of sound perception into the realm of spatial audio, particularly in the context of complex electronic compositions like Stockhausen's Oktophonie (1991). While a brief audio sample can reveal much about a traditional piece, it falls short when encountering works designed for immersive, multi-dimensional sound environments.

Oktophonie exemplifies how spatial audio can transcend the limitations of conventional recordings. Composed for an eight-channel system arranged in a cube, this piece doesn't merely play music; it sculpts the acoustic space itself. Each performance becomes a unique event, as the sound interacts with the specific characteristics of the venue, creating a sonic fingerprint that cannot be fully captured in a standard recording.

The experience of Oktophonie is akin to witnessing a living, breathing ecosystem of sound. Sound objects move, interact, and transform within the three-dimensional space, surrounding the listener in a dynamic audio environment. This spatial choreography adds layers of complexity beyond traditional musical elements:

- Spatial Dynamics: Sound sources move vertically and diagonally, as well as horizontally, creating a truly three-dimensional sonic landscape.

- Acoustic Interactions: As sound waves collide, they create complex interference patterns, emphasizing or cancelling each other out in ways unique to each space and listener position.

- Perceptual Transformation: The listener's perception constantly shifts as sound objects are born, evolve, and dissipate around them, creating a form of musical structure that exists in both time and space.

Just as a two-dimensional photograph cannot fully capture a sculpture, a stereo or even a multichannel recording struggles to convey the full dimensionality of Oktophonie. The piece demands presence within its carefully crafted sound field, where the listener becomes an active participant in a high-dimensional audio experience.

This approach to composition challenges our traditional notions of musical form and perception. It invites us to consider sound not just as a temporal phenomenon, but as a spatial entity that can be shaped, moved, and transformed in real-time. In essence, Oktophonie and similar works expand our auditory “DNA analysis” to include not just the content of the sound, but its behaviour in space and its interaction with the environment and the listener.

Ontology

In 1966 Pierre Schaeffer published Traité des objets musicaux elaborating on an idea he introduced a decade before in In Search of a Concrete Music: "A sound object is a sound in-itself". (Schaeffer et al. 2012 , p50)

The Sound Object

Pierre Schaeffer's concept of the sound object and reduced listening (l'écoute réduite) represents a significant shift in how we approach and understand musical sound. This ontological perspective on sound emphasizes its inherent qualities, divorced from its source or meaning. Schaeffer's “sound object” is a concept that views sound as an entity in itself, independent of its origin or context. This approach encourages listeners to focus on the intrinsic qualities of sound, rather than its referential aspects. The sound object is not the physical source of the sound, but rather the perceived acoustic phenomenon.

Reduced listening

Later, he introduced a particular form of listening that bypasses the semiotics of sound and attaches to a very particular phenomenological view: l'écoute réduite. According to Schaeffer, Edmund Husserl tells us that the object is immanent to all our sensory experiences through which we can approach using perception, imagination, desire, and memory. (Schaeffer 1988 , p160)

Ontological Implications

The French composer and engineer, gives us the example of two individuals approaching a mountain, their perception of the experience of the self and the other --who approaches the same mountain-- which is different, but belong to the same objective world: the world of objects. Surprisingly, in acousmatic music this approach can be only ontological as the sound object is static and there is a separation between the listener and sound. This separation manifests as a profound disconnection between the sound object and the listener, effectively preventing a truly immersive engagement with sound as an artistic experience. By restricting the listener's ability to explore the aesthetic dimension, acousmatic music renders the sonic encounter fundamentally static and ontologically distant, constraining the potential for a dynamic, transformative auditory interaction.

Schaeffer's approach has profound ontological implications for how we understand and experience sound:

-

Immanence: The sound object is immanent to our sensory experiences, accessible through various modes of consciousness1.

-

Objectivity: Despite subjective perceptions, sound objects belong to an objective world, similar to Schaeffer's mountain analogy.

-

Separation: In acousmatic music, this approach creates a separation between the listener and the sound, as there is no direct interaction with the sound's source

Schaeffer's concept of the sound object transcends individual experiences and emotional states. The object does exceed our individual experiences: the visual, auditory, tactile impressions and the way we interact with it through perception, memory, imagination, etc. Schaeffer defines the object as an independent thing that is perceived from a level that is deeper than the acousmatic reduction, and there is no need to interact or find its significance. This independence from subjective perception is crucial to Schaeffer's theory. (Schaeffer 1988 , p50)

The sound object, according to Schaeffer, exists at a level deeper than the acousmatic reduction. It is an autonomous entity that can be perceived without the need for interaction or interpretation of its significance. This approach aligns with Husserl's phenomenological method, which Schaeffer adapted to sonic analysis.

Reduced listening involves:

- Suspending preconceptions about the sound's source or meaning

- Focusing on the sound's inherent characteristics

- Analyzing the sound's (spectral) morphology and typology

By practising reduced listening, one can bypass the initial layer of significance that sounds typically impose, allowing for a more direct engagement with the sound object itself. This approach enables listeners to explore the full spectrum of sonic qualities, independent of their usual contextual or semantic associations.

Schaeffer's concept of the sound object and reduced listening, while groundbreaking, does indeed lead to some significant issues: The first one being concerned with the very definition of sound object, the second one pertaining to the limitations of the systems for the reproduction and spatialization of sound, which at the time, relied solely on psychoacoustics phenomena.1 Schaeffer ideas are contained to a particular mode of listening and composing shaped by the techné of the time. 2

Definition of the Sound Object

The separation between the physical and ontological aspects of sound creates challenges in defining the sound object precisely. This dichotomy raises questions about:

- The nature of the sound object's existence

- Its relationship to the physical world

- The extent to which it can be objectively analyzed

Limitations of Sound Reproduction Systems

The reliance on psychoacoustic phenomena for sound reproduction and spatialization at the time of Schaeffer's work presented several constraints:

-

Technological limitations: The audio technology of the era could not fully replicate the complex spatial and timbral characteristics of real-world sounds.

-

Perceptual discrepancies: The gap between physical sound properties and their perception led to challenges in accurately reproducing intended sonic experiences.

-

Spatial representation: Early spatialization techniques were limited in their ability to create convincing three-dimensional sound fields

Constraints of Schaeffer's Approach

Schaeffer's ideas were inherently shaped by the technological context of his time:

-

Limited listening modes: The focus on acousmatic listening and reduced listening restricted the exploration of other potential modes of sonic engagement1.

-

Technological determinism: The techné of the era heavily influenced Schaeffer's theoretical framework, potentially limiting its applicability to evolving sound technologies.

-

Exclusion of contextual elements: By isolating the sound object from its source and context, Schaeffer's approach may overlook important aspects of sonic experience and meaning. These issues highlight the need for a more comprehensive approach to understanding sound that integrates physical, perceptual, and contextual dimensions while acknowledging the evolving nature of sound technology and listening practices.

OOO

To address the limitations of Schaeffer's approach, we can turn to Object-Oriented Ontology (OOO), a philosophical framework that offers a fresh perspective on the nature of existence and relationships between objects. Developed by Graham Harman, OOO proposes a radical reevaluation of ontology that places all things at the centre of being Graham Harman, elaborating on some ideas after Heidegger, constructed a philosophical school of thought that allows us to equalize our relationship with other beings. (Harman 2011 , p5)

OOO posits a radical flattening of ontology: everything, from the sound emanating from a speaker to the listener perceiving it, is considered an object. This framework dissolves the traditional subject-object dichotomy, placing humans, animals, inanimate objects, and even concepts on the same ontological footing. While all entities are equally objects in this view, OOO introduces a nuanced hierarchy of reality. Some objects possess a more profound or enduring reality than others, creating a complex tapestry of existence where equality of status does not necessarily equate to equality of being. This perspective challenges us to reconsider our relationships with the world around us, including our interactions with sound and music. In OOO there is no distinction between object and what we call subject: they are both objects. All objects are equally objects, not all objects are equally real.

When we listen to acousmatic music, especially works in which sounds are derived from pre-recorded material (musique concrète) or synthesized sounds (elektronische musik), we can perceive several layers where sound objects interoperate. In acousmatic music, these layers become manifested in the form of timbre or spectral identity, loudness, movement and space. These units operate to convey something that structures our perception of the sound object. The relationships between these units are part of the aesthetic dimension, that is the dimension of causality. In OOO terms: “these inner ordinances or formulas of things withdraw; they are not grasped, even if they order perception like an imperative”. (Bogost 2012 , p27)

When we listen to a work of acousmatic music through loudspeakers we cannot bypass the ontological layer: it withdraws with the object, along with its aesthetic dimension. When we consciously hear without listening (Das Nur-herum-horen), there is a less understanding of the object, its inner relationships, its aesthetics. "The aesthetic dimension is the causal dimension” and art is an exploration of causality, which allows us to call a thing an object. (Morton 2013 , p20)

According to Heidegger, only he who already understands can listen. Any attempts to practice l'écoute réduite puts the Dasein in a state of privation of his understanding of being (everydayness) depriving the Dasein from an exploration of causality as an aesthetic phenomenon. From the point of view of OOO, these aesthetics events are not limited to interactions between humans and works of art. For example, aesthetics events are equally present in the relationship between someone listening to a helicopter above his head and someone listening to a recording of the helicopter, which is part of an acousmatic work that is perceived through loudspeakers.

The sound of a helicopter in a recording initially provokes an immediate referential association, following Pierre Schaeffer's listening paradigm. From a traditional perspective, a deeper level of listening emerges when one's attention shifts from the helicopter's representational meaning to the sound object itself. However, this approach fundamentally misunderstands the ontological nature of the sound object. As I said before, this perspective was inherently limited by the technological and aesthetic techné of its time, imposing a restrictive listening framework that constrains the listener and fails to comprehend the sound object's intrinsic characteristics. Furthermore, musique concrète remained embedded within the concert hall tradition, which predetermined audience interaction with music and sound. Pierre Boulez astutely recognized the complexity of this interpretive challenge and advocated for a multidisciplinary approach. He proposed radical changes, such as designing specialized concert halls without orchestras, attempting to dismantle the expansive nineteenth-century musical norms (Boulez and Nattiez 1986 , p448). Boulez's call for transformation has significantly influenced contemporary acousmatic music presentation. A telling example of the slow adoption of these innovative perspectives can be found in the premiere of Stockhausen's Gesang der Jünglinge at the WDR Funkhaus in 1956, where loudspeakers were positioned in a traditional concert hall, mimicking the arrangement of live performers.

To assume a meta position outside the object, as suggested by l'écoute réduite is impossible in an object-oriented universe. Synthesized sounds need the integrated circuit, the loudspeaker, the concert hall, the headphones and the composer. Sounds are made of more things than a portable recorder and the sound artist. A recording of the ocean is shaped by the surrounding landscape, a non-human intervention that is part of the work: causality. The rocks, the loudspeaker, and the concert hall are all part of the aesthetics of the object. Causality resides in the relations between objects and the relation of the object with itself, in places such as time and space. The aesthetic dimension is nonlocal and non-temporal. When two spectrally similar objects become closer in space, they become the same thing.

The exploration of space and time is an exploration of the object, and viewing the sound object form different space-time perspectives reveals the object's emergent properties. My argument is that l'écoute réduite deprives the listener from experiencing the aesthetic dimension of the object, and reducing the object to a stereo panorama (a psychoacoustic phenomena) creates a less-than-an-object that is deprived of its inner structure, undermining or hiding the aesthetic dimension which is critical in art. I see Schaeffer's sound objects as matter —reduced to “raw-materials-for”, as Timothy Morton puts it in Realistic Magic, being confined to an ontological prison, while objects in the spectral-spatialized domain emanate space, causality is emitted by objects, and the aesthetic dimension is truly exposed for the listener to interact.

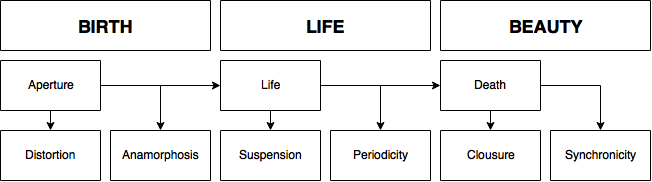

Exploring space and movement clarifies the aesthetic dimension of the object demarcating its temporal boundaries, its beginning and end. This relationship between movement and space (form) was firstly introduced by Karlheinz Stockhausen in Gesang der Jünglinge and had been the central point of my research in sound spatialization. (Jaroszewicz 2015 ) The electroacoustic composer can explore the aesthetic dimension of the sound object from its birth through its life and beauty. Being able to shape every aspect of the life of an object is an advantage for the composer working with spatialized electronic sounds. Spectral spatialization deals with every aspect of the life of the sound object by manipulating the relations between its inner layers. As the sound object moves and transforms, time emerges from the object finding its meaning in the future. Time and space are influenced by an object's spectral uniqueness, while at the same time, the aesthetic dimension is continuously transformed by these very time and space. To understand the object is to reveal its form. On the other hand, when sounds are spatialized without being affected by the spatio-temporal dimension, they seem to become obscure, they do not reveal causality and the work becomes a technological artifice: a display of no-object-sounds rotating around the listener. On the contrary, spectral spatialization adds meaning to the work by revealing the aesthetic dimension.

Spectral Spatialization

In the digital era, spectrum emerges as an ontological metaphor of sound and music. (Chagas 2014 , p43) The spectrum of a wave represents its frequencies and their relative amounts at a specific time in a two-dimensional format. By applying the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) algorithm to an audio file or audio stream, one can generate a spectrogram that reveals detailed information about the sound's inner components.

The connection between the concepts of space and time and the workflow of a composer working with spectra can be understood through the lens of Object-Oriented Ontology (OOO) and the transformative nature of sound in spectral music. The Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) algorithm detects periodicity in waves, allowing composers to analyze and manipulate sound spectra effectively. This manipulation is not merely technical; it embodies a creative process where the electroacoustic composer gives birth to spectral objects and spectral music. In OOO terms, the emergence of an object signifies its aperture, marking its unique occupation of space and time. When a spectral object is born, it displaces or deforms its environment, transforming the surrounding spectra by emphasizing certain frequencies while suppressing others. Timothy Morton articulates this idea, stating, "The birth of an object is the deforming of the objects around it" (Morton 2013 , p124). In the realm of spectral spatialization, this deformation manifests as a distortion within spectral space, where the interplay of sound creates a dynamic relationship between time and its sonic context. As composers engage with these spectral manipulations, they navigate a unique temporal landscape, where each sound evolves and interacts with its surroundings. The act of composing thus becomes a process of shaping both space and time through sound, allowing for an exploration of how these dimensions influence musical expression. This approach emphasizes that in spectral music, the manipulation of sound not only alters its immediate auditory characteristics but also redefines the spatial relationships within the composition itself, creating an intricate tapestry of evolving sonic experiences.

Morton refers to aperture as a feeling of uncertainty and distortion and causality being as a kind of sampling, a fragment that thereby creates another object. (Morton 2013 , p145) The metaphor of sampling translates directly into electroacoustic music. But instead of a chopped slice of tape, the electroacoustic composer can use granular synthesis, each grain of sound (approximately 50 milliseconds or fewer) becoming a new object that can be transformed and spatialized independently of the rest of the grains. The second stage on the life of an object is characterized by a sense of suspension and periodicity: the object repeats itself in time. In spectral spatialization, periodicity is not related to repetition, instead, periodicity of movement and location in space emerge as the object undergoes spectromorphological changes. Because sound objects return to the same point in space, there is a feeling of stasis that creates form shaped by periodicity and “the object is suspended between being-grasped and not-being-grasped”. (Morton 2013 , p162) At this point the object is infinite; the quality of not-being-grasped persists until the object dies, stopping emanating time, thus having no future.

The death of an object, or closure, occurs when it synchronizes with another object, fusing into a unified beauty as the listener tunes in to the sound. In frequency modulation, this phenomenon manifests when a carrier wave is modulated by a low-frequency oscillator (LFO), resulting in two sounds perceived as a vibrato effect; the two sounds blend into one. As the modulator's frequency increases, the sounds begin to separate, creating rich and complex spectra. As two sounds whose frequencies approach each other are heard, a beating effect becomes perceptible, most pronounced when they are less than 10 Hz apart, evoking a sense of impending annihilation. This concept of closure not only highlights the interaction between objects but also emphasizes the unique interplay of space and time within the composer's workflow. Each sound occupies its own distinct space and time, displacing or deforming its sonic environment as it interacts with others. In this context, the electroacoustic composer navigates a landscape where spectral manipulation shapes musical experiences that can transform the space. This transformation translates into a distortion within the spectral space, where the relationships between sounds evolve dynamically. The act of composing becomes a process of orchestrating these interactions, allowing for an exploration of how sound can transform both its immediate context and the listener's perception over time.

Techné

Among the various synthesis techniques that are well suited for spectral spatialization are cross-synthesis, granular synthesis and control-rate physical modelling. 3 In Compositional Strategies in Spectral Spatialization I have discussed different cross-synthesis techniques adapted for working in the spatio-temporal domain, as well as different tools to generate sound trajectories.

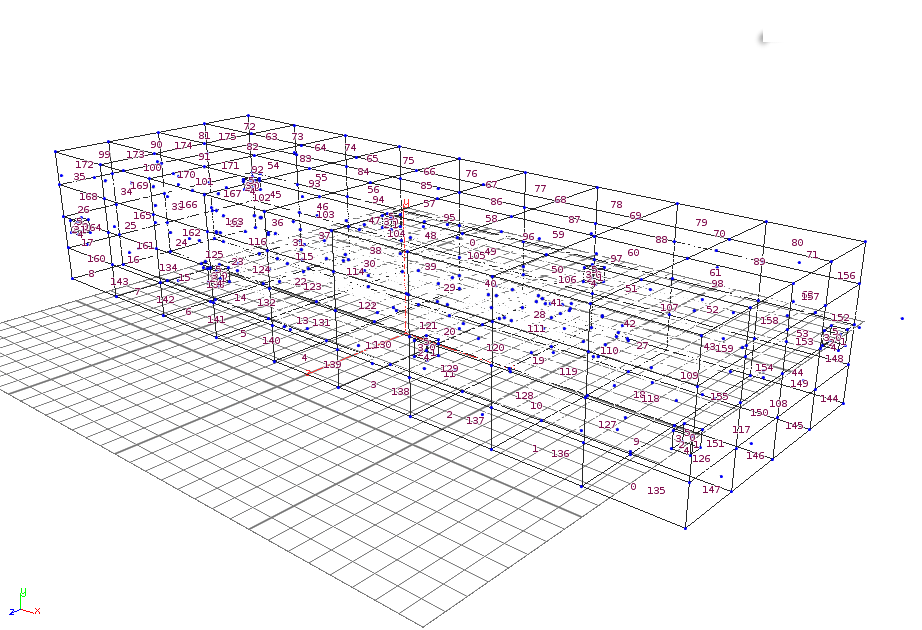

The concept of the sound grain, developed by Iannis Xenakis, serves as a foundational element in the field of granular synthesis, allowing composers to explore sound on a microtemporal scale. Xenakis postulated that all sound, even continuous musical variation, is composed of numerous elementary sounds that are organized in time. He articulated this idea by stating that "all sound is an integration of grains, of elementary sonic particles of sonic quanta. Each of these elementary grains has a threefold nature: duration, frequency, and intensity. All sound, even all continuous sonic variation, is conceived as an assemblage of a large number of elementary grains adequately disposed in time" (Xenakis 1971 , p43). This perspective laid the groundwork for granular synthesis, where small fragments of sound—referred to as grains—are generated and manipulated to create complex auditory textures. Granular synthesis can be effectively implemented using graphical data flow programming languages such as Pure Data (Pd) and Max/MSP. These platforms provide intuitive environments that enable composers to design and manipulate sound grains with precision. When combined with stochastic models, these tools can yield interesting results in the context of spatialization. For example, a random distributed point cloud can be spread through a virtual space that can be rendered using Wave Field Synthesis (WFS) or High Order Ambisonics (HOA).

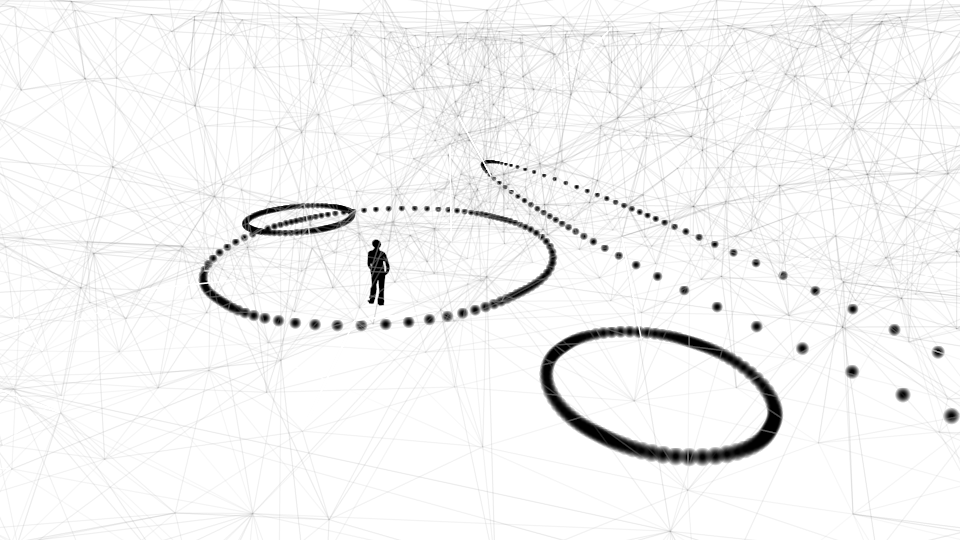

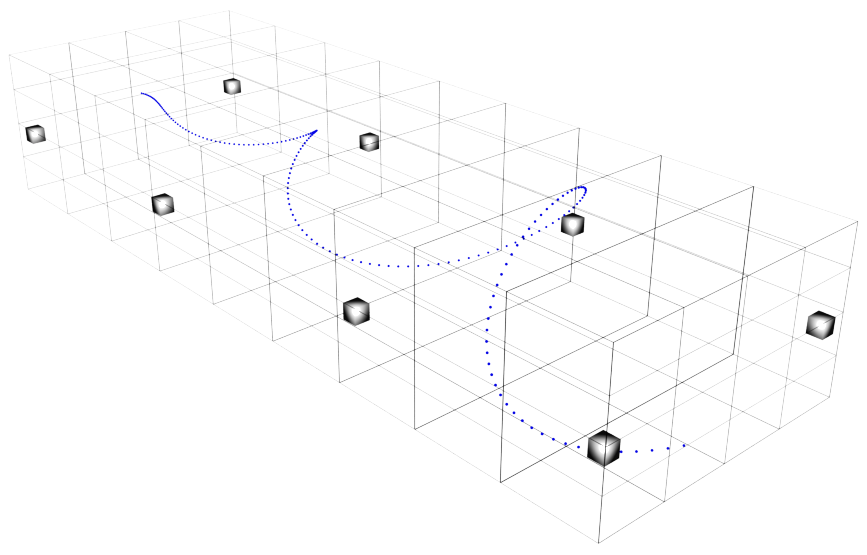

Granular synthesis and the concept of rotation are closely intertwined, as both involve the manipulation of sound in innovative ways that enhance the auditory experience. Granular synthesis operates by breaking sound into small fragments, or grains, typically lasting from a few milliseconds to a few hundred milliseconds. This technique allows for precise control over various parameters such as pitch, density, and duration, enabling composers to create complex textures and dynamic soundscapes. When integrating rotation into granular synthesis, the spatial movement of sound grains around the listener can significantly influence the perception of the auditory scene. By arranging these grains in circular or elliptical patterns, composers can create a sense of continuity and flow, as well as a feeling of stasis that synchronizes with the listener's experience. This rotational aspect not only enhances the immersive quality of the sound but also contributes to the formation of distinct musical accents and structures.

Using basic synthesis methods to create sound objects that rotate around the listener has been standard practice since Stockahusen's Rotationslautsprecher or Rotationstisch. This is an example of a techné that influenced many other compositions. (Manning 2006 , p87)

Circular or elliptical movement create a sense of stasis during the life of the sound object synchronizing with the listener creating form rather than a “passing” object that does not set into a regular rhythm or periodicity, thus becoming a musical accent. In music, cadenzas in piano concertos are often based on a sometimes unheard pedal point, a form of ontological suspension. The opposite would be the grace note which is an ornament not essential to harmony or melody in non-contemporary music.

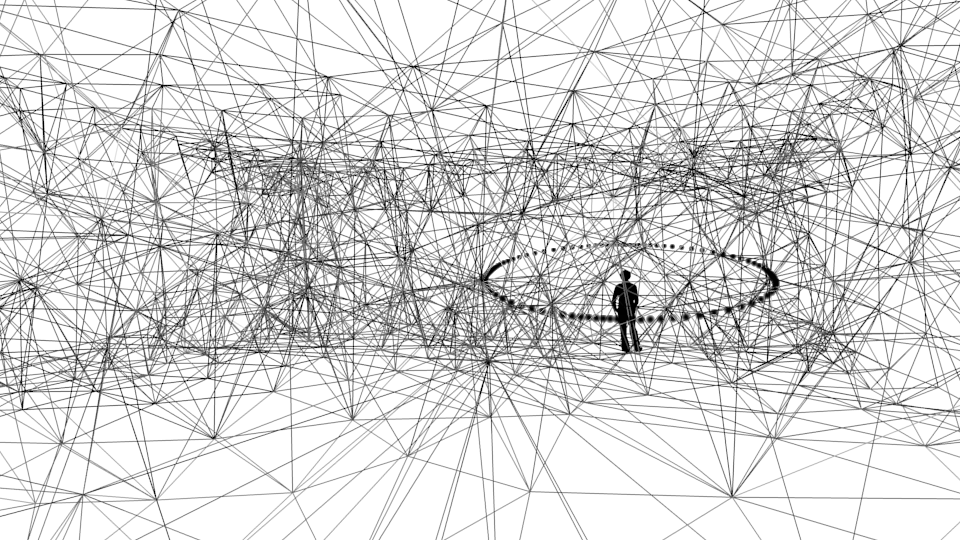

Figures 1 and 2 show the parallel in sound spatialization, a suspended and a passing object. (Jaroszewicz 2015 , p43)

Physical modelling algorithms that generate control data are particularly well-suited for spectral spatialization, as they allow for the creation of virtual physical structures that can fill a three-dimensional space. These structures act as control points for granular or additive synthesis, enabling composers to manipulate sound in a spatial context. By applying forces to individual points within these models, one can influence the surrounding area based on the rigidity of the connections or links between points, effectively creating a fabric or mesh of causality. The transition from rotational sound objects to physical modelling can be facilitated through the use of 3D animation software such as Blender or Houdini. These tools enable the design of complex geometries that represent sound-generating structures. The indices of vertices, faces, and edges within these models can be utilized as data inputs for sound synthesis and spatialization in real time. For instance, as sound grains are emitted from various points on a model, their movement can be controlled to follow specific trajectories, simulating natural phenomena such as vibrations or collisions. Moreover, the integration of physical modelling with granular synthesis allows for dynamic interactions between sound objects and their environment. As sound grains interact with the virtual physical structures, they can be influenced by simulated forces such as gravity, tension, or friction, leading to a rich and responsive auditory experience. This approach invites the composer to explore new creative possibilities in how sound is generated and perceived within a spatial framework.

Spectral spatialization implies synthesis and movement. In interactive media, particularly video games, creates an immersive 3D auditory experience that goes beyond traditional stereo sound. As players navigate virtual environments, they encounter dynamic soundscapes that respond to their movements and interactions. A binaural 3D space enhances the realism and depth of the gaming experience, allowing for precise sound localization and environmental awareness. Now consider the sound of a mosquito which we can only experience when the insect is very close to our ears.

Although a listening by reference of a stereophonic recording of a mosquito would never be convincing, the sensation of being surrounded by a mosquito can only be experienced through headphones using some sort of binaural technique. HOA and WFS allow for the same experience but instead of being individual, it is collective. Sound units and aesthetics are created in the synthesis domain and objects become beings in the spatialized domain. Listeners can experience the life of sound objects from within. When these objects are spatialized, they create form and add meaning to the work projecting into the audience a semiotic experience. For the listener, the work becomes an ontological appropriation, a trip from perception to an understanding of aesthetics and beauty: a transfiguration from sound object to Dasein. 4

Sound Hyperobjects

Mosquitoes are interesting because they produce high frequency sounds by flapping their wings at around 500Hz and a level of 55dB, depending on the behaviour. (LaurenJCator and R 2009 ) Suppose that you are in a rainforest and hear mosquitoes buzzing around your head. Can you count them only by listening? You might be able to hear how many mosquitoes are close to your body, but you might not be aware of the hundreds of thousands of mosquitoes swarming in the area, and that the swarm is a product of global warming. A swarm of mosquitoes is an example of a hyperobject.

The concept of a mosquito swarm as a hyperobject is intriguing. Hyperobjects, as described by philosopher Timothy Morton, are entities of such vast temporal and spatial dimensions that they defeat traditional ideas about what a thing is in the first place. A mosquito swarm, especially one influenced by global climate change, fits this description perfectly. It exists on a scale that transcends immediate human perception, has wide-ranging impacts across time and space, and is intricately connected to complex global systems.

The theory of hyperobjects developed by Timothy Morton to explain climate change and other ecological disasters can be used as a tool for a more profound understanding of the different qualities of sound objects. (Morton 2013 )

Hyperobjects are near us, but we cannot completely see them, we can perceive their shapes through causal experience and they seem to follow us like the mosquitoes in the rainforest or like the plane waves of a WFS system where sounds “follow” the listener who walks inside the array of speakers. (Jaroszewicz 2015 , p67) In OOO terms, hyperobjects are viscous; their life-span is unknown to us, and they are non-local, that is, phenomena manifest in places apart from the place of birth of the object.

The sound-hyperobject can be created using physical models that extend through a fabric of interconnected masses in the spatialized space. Sound hyperobjects differ in their way they are perceived by the listener by creating a sense of infiniteness (non-locality) as opposed to sound objects as localized points with unique coordinates in the listening space. When objects withdraw and phase in and out of the hearing threshold of the listener, he experiences sound the same way we experience icebergs; we only see part of a big entity. Sound hyperobjects phase because of their orbital paths and their life span cannot be grasped by the listener. Like distant comets that are yet to come to Earth, these particular sound objects whose path extends the listening space and revolve around a high dimensional space are sound hyperobjects. They surround the listener, but she is not able to perceive them in their totality. As sounds fade in an out, form is created pointing to a bigger structure that is non-local: A sound heard at p(x, y, z) is the result of the aesthetics and the working of inner units at some other point in the higher space.

Conclusion

Drawing from recent philosophical thought that puts objects at its centre, object-oriented ontology has been used in this article to provide a different perspective on the concept of the sound object firstly introduced by Pierre Schaeffer half a century ago. I have discussed the relationships between sound synthesis, movement, space and form in electroacoustic music, giving a theoretical and technical foundation for the digital music composer who wants to consider another dimension that can enrich the listening experience of the listener. As digital media is becoming a meaningless object, the use of sound objects in higher dimensional spaces allows the composer to provide a unique setting for the performance of his work, and to reestablish the ontological category that links, composer, sound, performance space and audience.

Many ideas and applications still have to be explored. Emergent technologies and interdisciplinary software research are changing the way we experience music and sound, and areas outside the music field can benefit from this research. The original idea of sound hyper-objects for spectral spatialization concerns sound synthesis, composition and psychoacoustics. The research poses questions such as: Is the time-varying spectra of a sound, a critical element in spatialized electroacoustic music? Is the listener capable of processing information about pitch, rhythm, and space in the context of hyper-objects? Research in localization of moving targets of varying spectra might be able to answer some of these questions, but there needs to be an ontological understanding a priori of the sound object, the apparatus (non-human phenomenology) and the effects of the interrelating emergent aesthetic relations of the units of operations of the objects. The proposed research topics go beyond electroacoustic music and the perception of sound in space. My current research has roots in OOO and the idea that space is not only the three dimensions we see. It explores the question whether space is a container for the aesthetic dimension.

January 9, 2016

-

The perception of a sound moving left to right on a stereo setup is a psychoacoustic phenomena that only works when the listener is at an equidistant distance from the two speakers. We localize sounds by their variations on their timbres and the different times of arrival of sound waves to our left and right ears. Two phenomena dictate the way we localize sounds: interaural time difference (ITD) and interaural intensity difference (IID). For a detailed explanation see Andy Farnell's Designing Sound. (Farnell 2010 , p79) ↩

-

For a discussion about the significance of techné see (Manning 2006 ). ↩

-

Data rate variables (k-rate) are updated once per control period unlike variables that are calculated and updated every audio sample (a-rate). ↩

-

I use the word transfiguration deprived of its religious connotation. ↩

Bibliography

Ian Bogost. Alien phenomenology, or, What it's like to be a thing. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 2012. ISBN 978-0-8166-7898-3 978-0-8166-8142-6. ↩

Pierre Boulez and Jean-Jacques Nattiez. Orientations: collected writings. Faber and Faber, London, 1986. ↩

Paulo Chagas. Unsayable Music: Six Reflections on Musical Semiotics, Electroacoustic and Digital Music. Leuvne University Press, Leuven, Belgium, 2014. ↩

Andy Farnell. Designing Sound. MIT Press, Cambridge, 2010. ↩

Graham Harman. The quadruple object. Zero Books, Winchester, U.K., 2011. ISBN 978-1-84694-700-1. ↩

Martin Jaroszewicz. Compositional Strategies in Spectral Spatialization. PhD thesis, University of California Riverside, 2015. ↩ 1 2 3

Laura C. Harrington Lauren J. Cator, Ben J. Arthur and Ronald R. Harmonic convergence in the love songs of the dengue vector mosquito. American Association for the Advancement of Science, 323(5917):1077–1079, February 2009. ↩

Peter Manning. The significance of the techn'e in understanding the art and practice of electroacoustic composition. Organised Sound, 11(1):81–90, 2006. ↩ 1 2

Timothy Morton. Hyperobjects: philosophy and ecology after the end of the world. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 2013. ISBN 978-0-8166-8922-4 978-0-8166-8923-1. ↩

Timothy Morton. Realist magic: objects, ontology, causality. Open Humanities Press, Michigan, 2013. ISBN 978-1-60785-202-5. ↩ 1 2 3 4 5

Pierre Schaeffer. Tratado de los objetos musicales. Alianza Editorial, Madrid, Spain, 1988. ISBN 978-84-206-8540-3. ↩ 1 2

Pierre Schaeffer, Christine North, and John Dack. In search of a concrete music. University of California Press, Berkeley, 2012. ISBN 978-0-520-26573-8 978-0-520-26574-5. ↩

Iannis Xenakis. Formalized Music: Thought and Mathematics in Composition. Indiana University Press, Indiana, 1971. ↩